Concurrency

Introduction

The objectives of this chapter is to go in depth about the different ways to do concurrency in ZIG.

We are first going to explore a few definitions and concepts that are going to be useful to understand the rest of the chapter. Then we are going to explore the different ways we could achieve concurrency in Zig. By the end you should be able to see the pros and cons of each solution and choose the one that fits your needs to develop your next Zig projects.

If you are not familiar at all the the concepts surrounding concurrency even though you should be able to follow along, I highly recommend reading Grokking Concurrency by Kiril Bobrov that I which I found before writing those chapters because it really sums up most of concurrency concepts really good.

Definitions

Before diving into the different ways to do concurrency in ZIG, let's first define some terms that are useful to understand the basics of concurrency that are not necessarly related to Zig. By the end of reading the definitions you should have a better understanding about the implementations we are going to see later.

It is important to note that the boundaries between some definitions are really blur and it is possible that you read a slightly different definition from an other source.

In this chapter we are going to consider that parallelism is a form of concurrency, meaning that concurency is having multiple parts of a programm running independently and parallelism is having multiple parts of a program running independently at the same time on multiple threads.

Coroutine

Courtines enable the management of concurrent tasks, coroutines themselves are not concurrent by nature but they are a tool to achieve concurrency. Their great power lies in their ability to write concurent tasks like you would write sequential code. They achieve this by yielding control between them. They are used for cooperative multitasking, since the control flow is managed by themselves and not the OS. You might see them in a lot of languages like Python, Lua, Kotlin with keywords like yield, resume and suspend.

Coroutines can be either stackful or stackless, we are not gonna dive deep into this concept since most of the time you are going to use stackful coroutines since they allow you to suspend from within a nested stackframe, the only strength of stackless coroutines is efficiency.

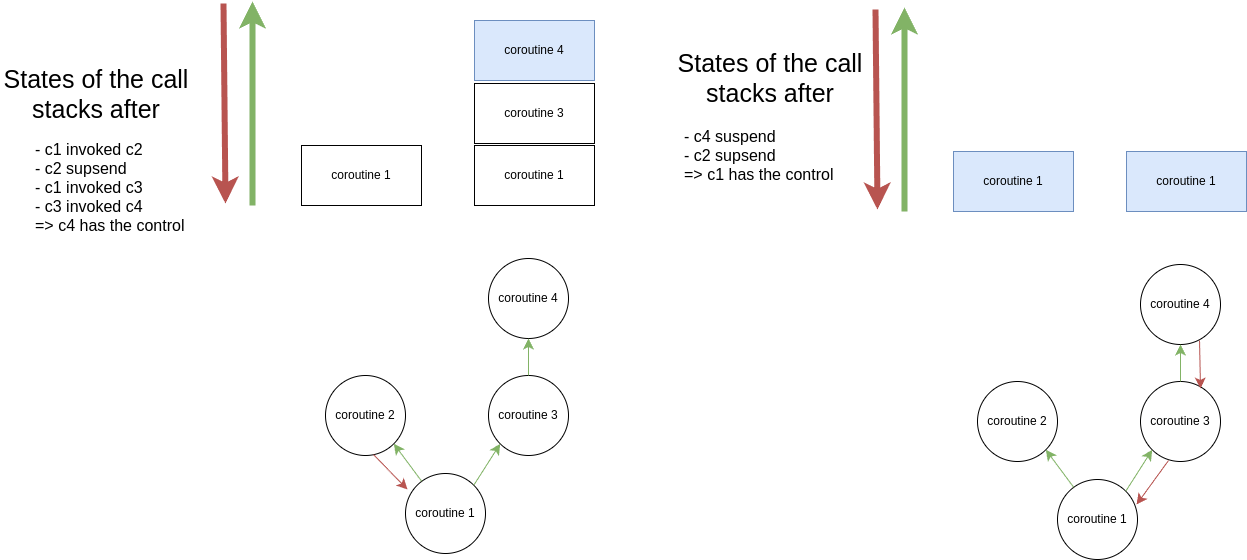

Symmetric coroutines

The only way to transfer the control flow is by explicitly passing control to another coroutine.

Asymmetric coroutines (called asymmetric because the control-transfer can go both ways)

- They have two control-transfer mechanisms:

- invoking another coroutine which is going to be the subcoroutine of the calling coroutine

- suspending itself and giving control back to the caller, meaning that the coroutine does not have to specifiy to which coroutine it is going to give the control back.

You can get more infromations about those 2 last concepts by reading this StackOverflow thread.

Green threads (userland threads)

Green threads, also known as userland threads are managed by a runtime or VM (userspace either way) instead of the OS scheduler (kernel space) that manages standard kernel threads.

They are lightweight compared to OS threads as they have a lower overhead (since it is managed in userspace instead of kernel). Even though they are not real OS threads, there are still OS threads that manage them under the hood. Paritculary useful for short-lived tasks. Green threads are most likely to be cooperative and yield control between them, even though it could be possible that they are managed by a runtime that has its own scheduler and can preempt them.

Green threads might be better for multiple short lived tasks (eg: web server) because of their low overhead when context switching and memory usage.

Be careful when using green threads not to use blocking functions, because blocking 1 green thread might mean blocking all the green threads because they most likely all run on the same kernel thread.

An other big advantage of green threads is that you do not have to synchronize them with concepts like mutexes since only one of them can run at a time, thus avoiding data races.

Preemptive multitasking

In preemptive multitasking it is the underlying architecture (not the process, but the OS or the runtime for exemple) that is in charge of choosing which threads to execute and when. This implies that our threads can be stopped (preempted) at any time, even if it is in the middle of a task.

This method gives the advantage of not having to worry about a thread being starved, since the underlying architecture is going to make sure that everyone gets enough CPU time. As we can see in the 2 graphs for preemptive and cooperative multitasking, the preemptive multitasking might context switch our tasks too much, which can lead to a lot of undersiable overhead.

There is an interesting thing that is happening in this graph, at the end we see that task 1 is only doing a very small job, which cost a context switch for almost no useful job, but the scheduler does not know that a task remains only a small job until done and can context switch it.

Cooperative multitasking

Contrary to preemptive multitasking, it is the progammer job to choose which and when the differents threads are executed. Threads are going to run until they are explicitly yielding control back.

This method gives the advantage to have the progammer to have a fine grained control over his ressources, but also implies that the programmer has to think about not starving threads.

In cooperative multitasking, we can yield the control back whenever we want, which leads to much less overhead compared to preemptive multitasking.

Kernel threads

Multithreading, it is the most basic and historical way to do concurrency, it works by running the work on multiple threads that are going to be exectued in parallel (if the CPU can), each thread runs independently of the others. Unlike asynchronous event-driven programming, threads typically block until their assigned task completes.

Threads are managed by the OS scheduler which is going to decide when to execute which thread.

Parallelism becomes achievable through multithreading (even though its not 100% guaranteed). Threads also offer robust isolation, with each thread possessing its own execution context, stack, and local variables, ensuring task independence and preventing interference.

However, scalability can become a concern when managing numerous threads. The overhead of resource allocation by the operating system kernel for each thread may lead to scalability issues, particularly in high-demand environments. This is the case because creating and destroying threads has a non-negligible cost, which can become a bottleneck when dealing with a large number of tasks.

To avoid this overhead, thread pools are often used, which manage a set of threads that can be reused for multiple tasks. This approach reduces the overhead of creating and destroying threads for each task, making it more efficient and scalable.

Event-driven programming

Event-driven programming, is basically an event loop that listen for "events". Under the hood this works by having an event loop that is going to poll for events and check regulary if an event has been emitted. Those events can be for exemple interupts or signals.

Asynchronous programming (non-blocking IO)

Asynchronous IO can be achieved by opening non-blocking sockets and then by using one of those 2 methods:

- polling systems (epoll, kqueue, …) that are going to poll frequently to see if a non-blocking call got its response back. Polling systems are better if there are a lot of IO operations, but less effective when less because they are going to poll for nothing most of the time. Not that you don't have to use those systems calls but you can do active listening by yourself by constantly checking if the non-blocking call is ready.

- events (interupts, signals, …) that are going to signal the caller that the response is is back and ready. Event-driven programming is less performant when the workload is high because interrupts have a big overhead.

When in this mode the execution flow of the program is unkown because we don't know when a non-blocking function might be ready for use and therefore take back the control flow of the application.

This method is useful if there a lot of IO operations, so that we can start processing other things while waiting for this IO operation.

You might think that threads can do that aswell and spawn a thread each time there is a blocking call, the thread is going to be put in non-ready mode until the blocking call is done and then re-ready, the thread wakes up and yield the result for exemple. It is true, threads can handle the job aswell, but the overhead of creating and managing a thread is much higher than the overhead of creating a non-blocking call. So when you have high workload, we generally prefer non-blocking IO calls.

A popular library that is used for asynchronous programming is libuv, the giant behind nodejs.

Under the hood libuv is basically a single threaded event-loop which is going to perform all IOs on non-blocking sockets that are polled by pollers like epoll or kqueue.

Zig solutions

We are now going to explore in the different chapters few different ways to achieve concurrency in Zig. We are going to see the pros and cons of each solution and when to use them.