Kernel threads

Basics

Spawning OS threads in Zig is quite simple, since it is built-in in the standard library. Here is an example of how to spawn 2 threads that are going to print numbers from 0 to x in parallel:

pub fn main() !void {

const thread1 = try std.Thread.spawn(.{}, goTo, .{ 1, 5 });

const thread2 = try std.Thread.spawn(.{}, goTo, .{ 2, 3 });

thread1.join();

thread2.join();

}

fn goTo(thread_id: u8, max: usize) void {

var i: u32 = 0;

while (i <= max) {

std.debug.print("{} = {}\n", .{ thread_id, i });

i += 1;

}

}Note that the std.Thread also offer few other useful functions like std.Thread.getCpuCount() to get the number of CPU cores available on the machine.

std.debug.print("Total CPU cores = {!}\n", .{std.Thread.getCpuCount()});Thread pool

You could also use a thread pool in order to have a few threads to multiple jobs and not a thread per job.

pub fn main() !void {

var gpa = std.heap.GeneralPurposeAllocator(.{}){};

defer _ = gpa.deinit();

const allocator = gpa.allocator();

var pool: std.Thread.Pool = undefined;

try pool.init(.{ .allocator = allocator, .n_jobs = 2 }); // if you dont set n_jobs it is simply going to use the total number of cores in your system, but alloactor is obligatory.

defer pool.deinit();

for (0..8) |i| {

try pool.spawn(goTo, .{ @as(u8, @intCast(i)), 3 });

}

}

fn goTo(thread_id: u8, max: usize) void {

var i: u32 = 0;

while (i <= max) {

std.debug.print("{} = {}\n", .{ thread_id, i });

i += 1;

}

}Implementation in the std

Under the hood the threads are either pthread (if we are under linux AND linking libc) or it is simpy going to use native OS threads (syscalls) wrapped by a Zig implementation.

The advantage of doing multi-threading in Zig is that you don't have to worry about what the target system is going to be, since std.Thread implementation automatically chooses the native OS threads for the system your are compiling for, except if you want to enforce the use of pthreads by linking the libc.

In C if you are using Windows for exemple, since pthreads it is not natively supported you would have to use a third-party implementation by adding a compilation flag like so:

gcc program.c -o program -pthreadOr worse, you would have to use a completly different library ending up with a lot of pre-processor directives to check if you are using Windows or not which is going to lead to messy code:

#include <stdio.h>

#ifdef _WIN32

#include <windows.h>

#else

#include <pthread.h>

#endif

#ifdef _WIN32

DWORD WINAPI ThreadFunc(LPVOID lpParam) {

printf("Thread running...\n");

return 0;

}

#else

void *ThreadFunc(void *arg) {

printf("Thread running...\n");

return NULL;

}

#endif

int main() {

#ifdef _WIN32

HANDLE hThread;

DWORD dwThreadId;

hThread = CreateThread(NULL, 0, ThreadFunc, NULL, 0, &dwThreadId);

if (hThread == NULL) {

printf("Failed to create thread.\n");

return 1;

}

// Wait for the thread to finish

WaitForSingleObject(hThread, INFINITE);

// Close the thread handle

CloseHandle(hThread);

#else

pthread_t thread;

int rc;

rc = pthread_create(&thread, NULL, ThreadFunc, NULL);

if (rc) {

printf("Failed to create thread. Return code: %d\n", rc);

return 1;

}

// Wait for the thread to finish

pthread_join(thread, NULL);

#endif

printf("Everything is done.\n");

return 0;

}Or you could write your own wrapper kind of like the way Zig does, note that is code is pseudo-code and is not executable:

#include <stdio.h>

#ifdef _WIN32

#include <windows.h>

#else

#include <pthread.h>

#endif

int myCreate(unsigned long *thread, void *func) {

#ifdef _WIN32

return hThread = CreateThread(NULL, 0, func, NULL, 0, thread);

#else

return pthread_create(thread, NULL, func, NULL);

#endif

}

void myJoin(unsigned long thread) {

#ifdef _WIN32

return WaitForSingleObject(thread, INFINITE);

#else

pthread_join(thread, NULL);

#endif

}

void *ThreadFunc(void *arg) {

printf("Thread running...\n");

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t thread; // TODO I should also wrap that which is pthread specific

int rc = myCreate(&thread, ThreadFunc);

if (rc) {

printf("Failed to create thread. Return code: %d\n", rc);

return 1;

}

myJoin(thread);

printf("Everything is done.\n");

return 0;

}Zig pthreads vs LinuxThreadImpl vs C pthreads

When compiling on Linux, by default your threads are going to use the LinuxThreadImpl. Which under the hood simply is a wrapper around some syscalls in order to manage threads (the code does closely the same thing as the pthread code).

You might have notice that when you are linking libc, Zig is going to use pthreads instead of the LinuxThreadImpl. This is because pthreads are more performant at the moment and since you are already linking libc it is better to take advantage of that and ue pthreads.

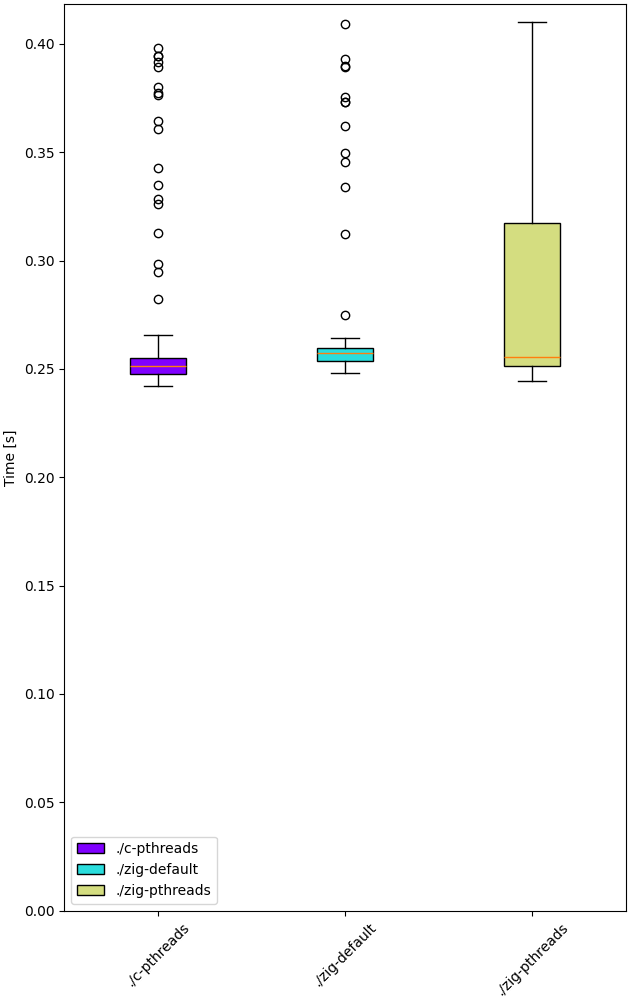

In order to verify that we are going to benchmarks 3 different implementations: one in Zig using LinuxThreadImpl, one in Zig using pthreads and one in C using pthreads.

The way we are going to measure which implementation is better is by comparing the time it takes to spawn and destory N threads. It is useless to do work in the threads because no matter the implementation they are going to execute in the same way. It might even be counter-productive because you are going to start comparing the code inside the threads instead of the threads themselves.

Note that it is hard to benchmark thread implementations and you can easily end up not directly benchmarking them, if you for exemple try to compare the number of context switches between 2 implementations. Context switch happen randomly whenever the OS scheduler wants it. So trying to analyze that might lead you into false conclusions.

const std = @import("std");

const NB_THREADS = 10000;

pub fn main() !void {

var threads: [NB_THREADS]std.Thread = undefined;

for (0..NB_THREADS) |i| {

threads[i] = try std.Thread.spawn(.{}, goTo, .{});

}

for (0..NB_THREADS) |i| {

threads[i].join();

}

}

fn goTo() void {}If we run this code with hyperfine (100 runs) once while linking libc (using pthreads),once in vanilla mode (using LinuxThreadImpl) and a list time using pthreads with C, we can see that they overlap in the measure variablity, so we can conclude that the performances probably will not change between the different implementations:

- Zig pthreads = 274.4 ms += 4.7 ms

- LinuxThreadImpl = 276.7s ms += 33.9 ms

- C pthreads = 272.7 ms += 34.0 ms

I tried having 100'000 threads instead of 10'000 in order to get a bigger N but I ran out of memory.

Those test have been run multiple times on different days and the results can vary a bit, but all the implementations can beat each others from time to time, since it is heavily dependent on the OS scheduler and not the thread implementations themselves.

The difference is so small that even when only spawning and destroying threads we barely see it. In a real world application where this would very unlikely be the bottleneck, which thread implementation you are going to use is very likely to not change anything the way your program perform.

We can then conclude that there is an almost zero cost abstraction when using threads in Zig. Which is very good for high performances applications.

Thread synchronization

Threads can be synchronized with utilities that are the same as most other languages (notably C). So when jumping in the std doc you should not be suprised and understand most of the features like Mutex and Semaphore.

Here is the Zig code:

const std = @import("std");

var common: u64 = 0;

var m = std.Thread.Mutex{};

pub fn main() !void {

var gpa = std.heap.GeneralPurposeAllocator(.{}){};

defer _ = gpa.deinit();

const allocator = gpa.allocator();

var pool: std.Thread.Pool = undefined;

try pool.init(.{ .allocator = allocator });

for (0..1000) |_| {

try pool.spawn(goTo, .{});

}

pool.deinit();

std.debug.print("{d}", .{common});

}

fn goTo() void {

m.lock();

common += 1;

m.unlock();

}And the equivalent C code:

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define NB_THREADS 10000

pthread_mutex_t mutex;

unsigned long long common = 0;

void* goTo(void* arg) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&mutex);

common += 1;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&mutex);

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t threads[NB_THREADS];

int i;

if (pthread_mutex_init(&mutex, NULL) != 0) {

printf("Mutex initialization failed\n");

return 1;

}

for (i = 0; i < NB_THREADS; i++) {

if (pthread_create(&threads[i], NULL, goTo, NULL) != 0) {

printf("Thread creation failed\n");

return 1;

}

}

for (i = 0; i < NB_THREADS; i++) {

pthread_join(threads[i], NULL);

}

pthread_mutex_destroy(&mutex);

printf("%llu\n", common);

return 0;

}Leaky abstraction

There are 2 things you can tweak when using std.Thread: the stack size and the allocator.

The allocator you pass is only going to be needed if you use the WasiThreadImpl (which is the default implementation for WebAssembly). The reasons for that is that it needs the allocator to dynamically allocate the eventuals metadata that are going to be used by the thread. Here is the code where you can see that.

fn spawn(config: std.Thread.SpawnConfig, comptime f: anytype, args: anytype) SpawnError!WasiThreadImpl {

if (config.allocator == null) {

@panic("an allocator is required to spawn a WASI thread");

}

...

}You wont't have to free it anyway since it is only used to be copied like we can see in the source code of the std.Thread:

// Create a copy of the allocator so we do not free the reference to the

// original allocator while freeing the memory.

var allocator = self.thread.allocator;

allocator.free(self.thread.memory);However, configuring the stack size is going to be used for every implementation of the threads. This is the default stack size:

/// Size in bytes of the Thread's stack

stack_size: usize = 16 * 1024 * 1024So if you need to modify it in order to store more local variables, pass more arguments, … in order to avoid a stack overflow. Don't put that value too hight either, because you might not have enough space to create a lot of threads after that. Note that there are currently talks about making the stack size known at compilation time and make it only uses what is needs, making the stack size very small compared to that default.

If you want to fine grained your thread further (eg. thread priority) you might need to use the C pthread library, which allow for a ton of possiblites of tuning. Note that when using std.Thread you are going to have almost everything set to the default of your implementation. For exemple the only thing that is tuned when using the PosixThreadImpl is the guard size.

assert(c.pthread_attr_setguardsize(&attr, std.mem.page_size) == .SUCCESS);Which corresponds to

pub const page_size = switch (builtin.cpu.arch) {

.wasm32, .wasm64 => 64 * 1024,

.aarch64 => switch (builtin.os.tag) {

.macos, .ios, .watchos, .tvos, .visionos => 16 * 1024,

else => 4 * 1024,

},

.sparc64 => 8 * 1024,

else => 4 * 1024,

}Conclusion

Zig threads are really useful since they have a very user-friendly abstraction with not a lot of functionalites that are almost never used anyway. This abstraction is also very useful for what we saw earlier, you don't have to worry about the target system, Zig is going to choose the right implementation for you.

But this leaky abstraction comes at a cost, you can not fine-tune your threads as much as you would like to.

If you need specific thread functionalities, like the ones we talked about, you can still do that in Zig by wrapping the C pthread library for exemple or directly use the OS native threads you want.

If your application is using a lot threads for handling each new connection on a TCP server for example you might thinking about switching to another non-blocking solution, the main reason being that threads are quite heavy and have a non-negligeable overhead because they act like a process and have their own stack.